Star polygons

Categories: gcse geometry

Level:

We looked at star polygons in a previous article. We will now look at them in more detail.

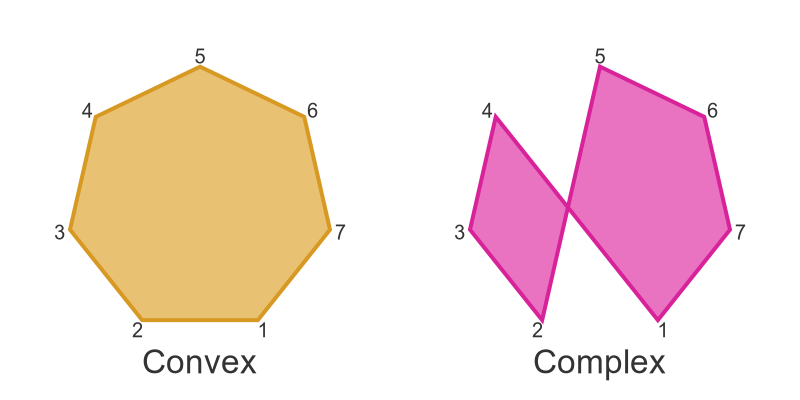

We saw that some polygons are self-intersecting, that is some of their sides cross over each other, like the shape on the right, here:

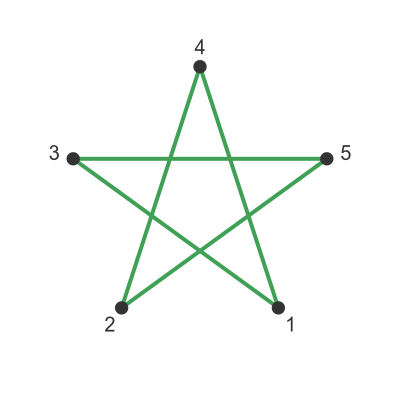

Self-intersecting polygons are called complex polygons. A star polygon is a type of complex polygon that creates a star shape. Here is an example of a 5-point star:

This is called a pentagram (a pentagon is a 5-sided convex polygon, a pentagram is a 5-sided start polygon). It is formed from the same 5 points that would be used to draw a convex polygon, but we connect the points in a different order to create the star shape.

In this case, the vertices we are using are from a regular pentagon (all 5 sides and all 5 angles are equal). The star shape is therefore a regular pentagram (which again has 5 equal sides and 5 equal angles, but they are different to the pentagon).

We will look at some other regular star polygons and their properties below.

Regular pentagrams

The pentagram above is formed by taking the 5 points of a regular pentagon, but connecting them in the order 1, 3, 5, 2, 4 (then back to 1).

In each case starting at vertex 1, we connect to the second vertex along in the clockwise direction:

- Vertex 1 connects to vertex 3

- Vertex 3 connects to vertex 5

- Vertex 5 connects to vertex 2 (because we have gone all the way round the points and the count starts at 1 again)

- Vertex 2 connects to vertex 4

- Vertex 4 connects back to vertex 1, so the cycle is complete.

We can use a special notation for this star polygon. We call it {5/2}, meaning there are 5 vertices and we will form the star by stepping on 2 vertices each time.

You might guess that there are other possibilities:

- {5/1} 5 vertices, stepping on by 1 each time.

- {5/2} we have just seen.

- {5/3} stepping on by 3 each time.

- {5/4} stepping on by 4 each time.

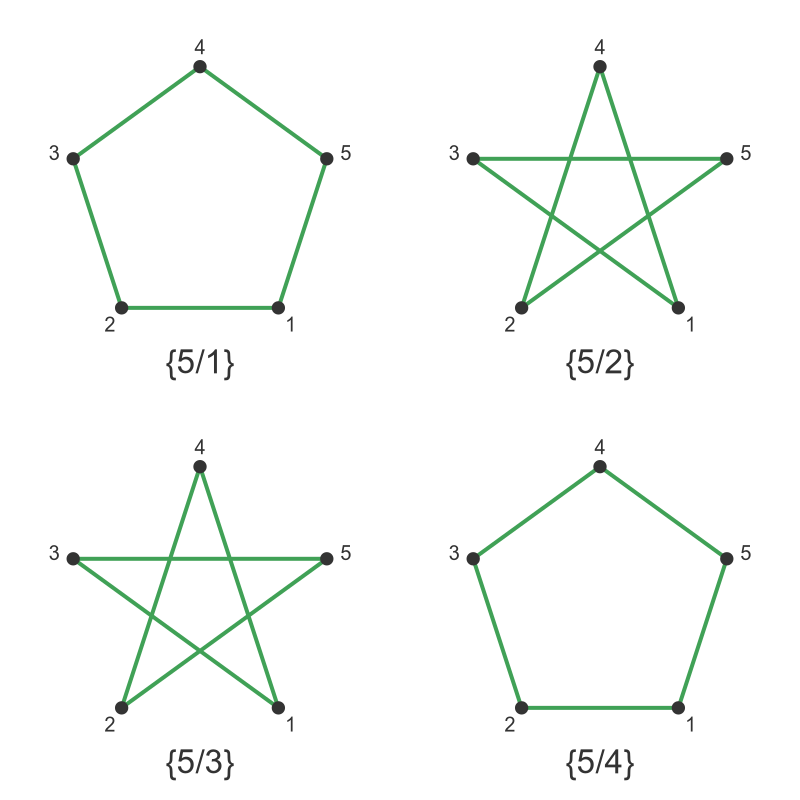

Those are the only possibilities. {5/5} won't work because if we start at point 1 and step round 5 points we will be back at point 1. {5/6} means stepping on by 6 each time, which is a full circle plus 1, so it creates the same result as {5/1}, and so on. There are only 4 possible options for a 5-pointed star. Here is what they look like:

The {5/1} case steps through the points in the order 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 - in other words, it just creates a normal regular pentagon.

The {5/3} case looks identical to the {5/2} case. Why should that be? Well making 3 steps clockwise is the same as making 2 steps counterclockwise, so {5/3} is the mirror image of {5/2}. Since {5/2} is symmetrical that makes the results identical.

Following the same logic, {5/4} creates the same result as {5/1}.

This means that there is only one type of regular star pentagram.

General rule

For a regular polygon with s sides:

- Type {s/1} will be a convex polygon (that is, an ordinary regular polygon). Example {5/1} is a regular pentagon.

- Type {s/n} will be identical to type {s/(s-n)}. Example {5/2} is same shape as {5/3}.

- Type {s/(s-1)} will be a convex polygon (from the second rule). Example {5/4} is a regular pentagon.

Regular hexagrams

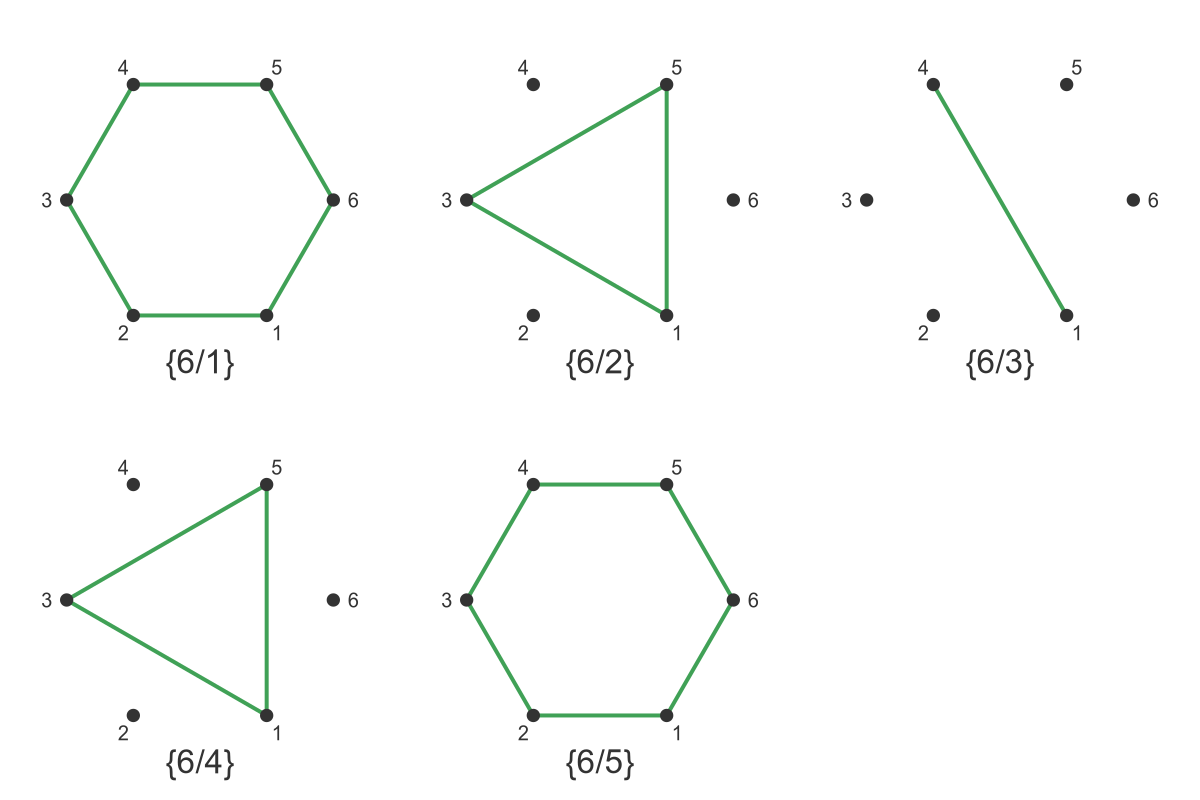

We can do the same thing with hexagons. Here are the 5 possibilities for {6/1} to {6/5}:

First of all, as we would expect from the rules, {6/1} and {6/5} are regular hexagons. And {6/2} is identical to {6/4}.

The only unique cases we need to consider are {6/2} and {6/3}.

But something strange is happening here. The {6/2} case doesn't visit all the points. It creates a triangle of points 1, 3, and 5. The reason for this is that 6 and 2 contain a common factor - they are both divisible by 2. Starting from point 1 there is no way to reach an even-numbered point by repeatedly adding 2.

The {6/3} case is even worse. It creates a line between points 1 and 4. The reason again is that 6 and 3 contain a common factor - they are both divisible by 3. Starting from 1 and adding 3 we get to 4, and then back to 1.

So, there are no star polygons with 6 sides.

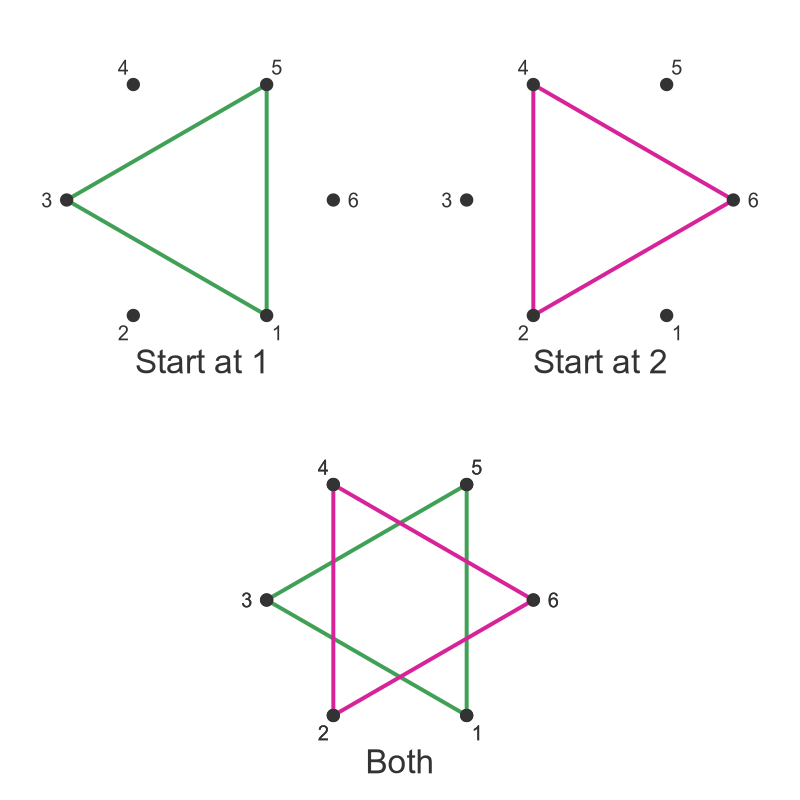

We can create a kind of star, like this:

There are two possible triangles we can create with a {6/2} shape. Starting at point 1 we visit points 1, 3, and 5. Starting at point 2 we visit 2, 4, and 6. If we draw both triangles together we get a star shape. However, this is not a star polygon because it is formed from two separate triangles.

The fancy name for this is a stellation. This is a star shape created by one or more polygons that visit every vertex. {6/2} is a stellation made up of 2 triangles. {5/2} is a stellation made up of a single pentagram.

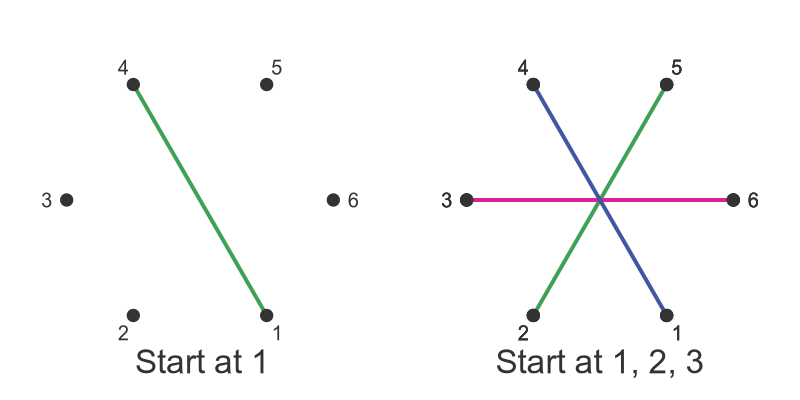

We can do a similar trick in the {6/3} case, this time including 3 lines starting at points 1, 2 and 3. Here is the result:

Regular heptagrams

What about a 7-point star polygon?

Let's use what we have learned already to reduce the number of cases we have to look at:

- {7/1} and {7/6} will create a normal convex heptagon.

- {7/2} should create a star because 7 and 2 have no common factors (no number divides into both 7 and 2).

- {7/3} should create a star because 7 and 3 have no common factors.

- {7/4} will be identical to {7/3}, and {7/5} will be identical to {7/2}.

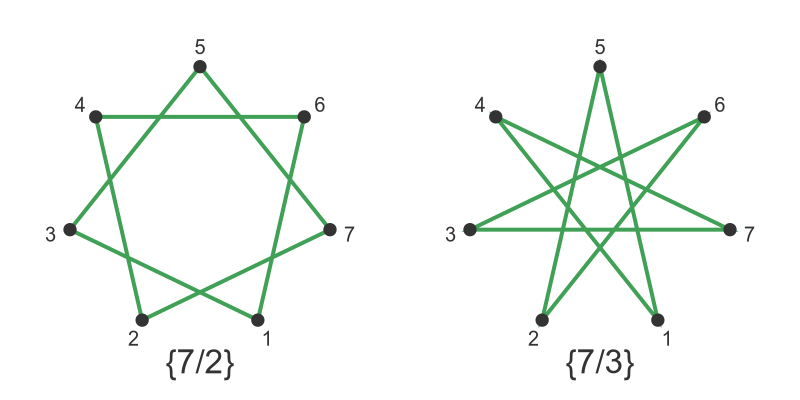

So there are only 2 cases we need to look at:

As predicted, both of these are proper star polygons.

Larger numbers of sides

The same logic can be applied to any number of sides. In many cases, the shape will have one or more types of star, but also some cases that don't create a star.

Related articles

- Regular polygons

- Interior and exterior angles of a polygon

- Triangles

- Quadrilaterals

- Quadrilateral family tree

- Pentagons - polygons with 5 sides

- Hexagons - polygons with 6 sides

- Heptagons - polygons with 7 sides

- Octagons - polygons with 8 sides

- Nonagons - polygons with 9 sides

- Decagons - polygons with 10 sides

- Hendecagons - polygons with 11 sides

- Dodecagons - polygons with 12 sides

- n-gons - polygons with any number of sides

- Other types of polygon

Join the GraphicMaths Newsletter

Sign up using this form to receive an email when new content is added to the graphpicmaths or pythoninformer websites:

Popular tags

adder adjacency matrix alu and gate angle answers area argand diagram binary maths cardioid cartesian equation chain rule chord circle cofactor combinations complex modulus complex numbers complex polygon complex power complex root cosh cosine cosine rule countable cpu cube decagon demorgans law derivative determinant diagonal directrix dodecagon e eigenvalue eigenvector ellipse equilateral triangle erf function euclid euler eulers formula eulers identity exercises exponent exponential exterior angle first principles flip-flop focus gabriels horn galileo gamma function gaussian distribution gradient graph hendecagon heptagon heron hexagon hilbert horizontal hyperbola hyperbolic function hyperbolic functions infinity integration integration by parts integration by substitution interior angle inverse function inverse hyperbolic function inverse matrix irrational irrational number irregular polygon isomorphic graph isosceles trapezium isosceles triangle kite koch curve l system lhopitals rule limit line integral locus logarithm maclaurin series major axis matrix matrix algebra mean minor axis n choose r nand gate net newton raphson method nonagon nor gate normal normal distribution not gate octagon or gate parabola parallelogram parametric equation pentagon perimeter permutation matrix permutations pi pi function polar coordinates polynomial power probability probability distribution product rule proof pythagoras proof quadrilateral questions quotient rule radians radius rectangle regular polygon rhombus root sech segment set set-reset flip-flop simpsons rule sine sine rule sinh slope sloping lines solving equations solving triangles square square root squeeze theorem standard curves standard deviation star polygon statistics straight line graphs surface of revolution symmetry tangent tanh transformation transformations translation trapezium triangle turtle graphics uncountable variance vertical volume volume of revolution xnor gate xor gate